Funded by a £1.2 million grant made possible by players of People’s Postcode Lottery, Space4Nature is a partnership between Surrey Wildlife Trust, the University of Surrey, Buglife and the Painshill Park Trust, which aims to map Surrey’s habitats more accurately than every before. Using the latest satellite earth observation imagery and artificial intelligence alongside citizen scientists on the ground, it will enable the Trust to work with landowners across the county to create, restore and connect fragmented habitat and support healthier biodiversity.

Satellites, AI... and hand lenses

Andrew Jamieson

SWT S4N Project Manager

This is a multifaceted project with many moving parts and I'm extremely pleased with progress to date. The University of Surrey is focusing on mapping, observation data, and machine learning. Buglife's B-Lines has already reached its overall project target for habitat restoration. And here at SWT our citizen science programme has been fantastic. We've trained dozens of volunteers on survey methodology and our S4N app, and we've completed many surveys.

We've been adapting as we go. Our original bid presented an eye-catching idea, but we had many details to iron out. Some of my major responsibilities have been to agree the overall project plan and define the right outcomes and KPIs (key performance indicators that measure progress over time for a specific objective). Taking a partnership approach naturally means we have all learned to accommodate others' ways of working, from academic to entrepreneurial. Different organisations have different styles, timelines, and stakeholders. I'm also struck by the level of external interest, including from other partnerships and public bodies. We talk regularly to other Wildlife Trusts, NGOs, National Parks and so on.

The word is spreading. The project's wider effects are also potentially significant. It has boosted our own research and monitoring team and promoted the use of technology. However, while many people are using satellite technology in conservation, for me citizen science is the key difference that can deliver accurate mapping and aid landscape recovery and connectivity. Meanwhile, we are also working with The Land App, which provides easy-to-use technology for landowners and managers to map their land. It's a gateway to a huge constituency of users, from farmers to water companies, who already use it to plan interventions and access funding.

Dr Ana Andries

Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Centre for Environment and Sustainability, University of Surrey

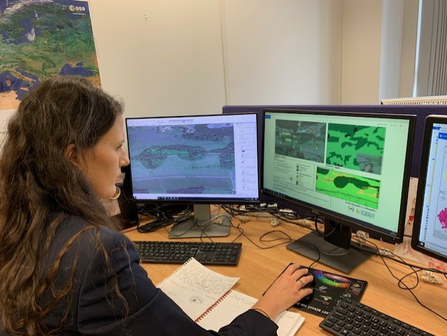

My role is primarily technical: to combine the power of artificial intelligence and machine learning with satellite imagery, so we can rapidly identify and match habitats on a large scale. However, to make this work, the ‘ground truth’ that comes from citizen science is priceless.

Essentially, the AI learns to recognise different habitats by understanding patterns of spectral reflectance in the satellite imagery, which we match to observations on the ground. Together this data helps us efficiently create accurate habitat maps. To date we’ve made promising progress on chalk grassland and heathland distribution – and we’re continually refining the models to make them more accurate.

So far we have been making predictions about habitat quantity; next we will look at its quality, which requires a new methodology. We need to collect data from more sites to better understand the variables. Combined with quantitative data, this will feed into our understanding of biodiversity net gain (BNG), which property developers are now obliged to deliver as a condition of planning permission. Already we know this is the most accurate mapping method we’ve ever had – and one that DEFRA and ecologists can rely on.

About the satellites

Space4Nature uses images from the PlanetScope mission launched by Planet Labs, part of the European Space Agency. The mission comprises more than 430 different satellites, which circle the Earth every 90 minutes at relatively low orbit (c500km). The satellites each weigh less than 6kg and measure 10x10x30cm. Together they can image almost all the land on Earth every day. They use spectral reflectance to remotely identify and measure different types of vegetation. Planet Labs provides this data free of charge to the S4N project, as it is for academic and research purposes.

For more information visit earth.esa.int/eogateway/missions/planetscope

© Surrey Wildlife Trust

Mike Waite

SWT’s Director of Research and Monitoring

Having been involved in selecting our test sites, I’m glad that we haven’t had many unexpected results so far – although the Earth Search bioblitz at Painshill Park last summer was even better than we hoped, with some 300 species identified. In general, we chose heathland and chalk grassland that proved to be representative of their respective habitats. The ultimate prize is an accurate understanding of habitat quantity and distribution right across Surrey. Our current picture is flawed and S4N offers a new way to remotely interpret data and provide information that is essential for connectivity modelling.

At this early stage we’re still seeing some anomalies, when the technology misrecognises a particular type of grassland, but this only helps us refine it. There are many factors to consider, such as weather conditions and time of year. In some cases, we are trying to find the sweet spot – the narrow window when a specific habitat is most easily identified. Land managed by SWT, National Trust and other conservation organisations is already well documented, which is why we use it as test sites. The critical shift is to extrapolate onto private estates, where there are huge opportunities to improve things for wildlife.

These landowners tend to be receptive to the idea of acting for nature, as long as you can show them the data. With environmental policy and subsidies still in flux after Brexit, this is the ideal time to advocate with them. As for improving the prospects of particular species, I could name three flagships that will certainly benefit from our work: Dormouse for woodland; Adonis Blue butterfly for chalk grassland; and Adder for heathland and acid grassland. All three tend to be on fragmented sites, with a limited dispersal range, so better connectivity will be vital for their prospects.

Louis Harrington-Edmans

Space4Nature Conservation Officer, Buglife

Buglife’s practical conservation work in the UK includes B-Lines, a beautiful solution to the problem of the loss of flowers and pollinators through habitat fragmentation. It involves restoring and creating 3km-wide lines of wildflower-rich habitat through countryside and towns to provide connectivity for invertebrates and other wildlife.

Being part of S4N has enabled us to deliver this for the first time in Surrey – and the results are spectacular. Halfway through the project, we have already beaten our target of 30ha of new, restored, or enhanced B-Line habitat. From now on, we aim to keep up the momentum, reach out to more landowners, and refine our site selection. The machine-learning feedback loop inherent in S4N helps us monitor the impact of our efforts.

As the project continues, we’re learning how to address a range of different sites, from nature reserves to community green spaces, and to work with private landowners, such as Painshill Park Trust, conservation NGOs, and local authorities. For example, we’ve recently overseen reseeding at Tyting Farm near Guildford and scrub clearance at Quarry Hangers.

Above all, working with our S4N partners is a wonderful opportunity to learn. We don’t always agree on everything, but we have the same overarching goal: to improve Surrey’s habitats for nature.

Dan Banks

SWT Citizen Science Officer

Sometimes I meet people who are deterred from volunteering with SWT because they think it may be too physically challenging. This project is a great example of how we welcome everyone, whatever their age, physical strength, or mobility – we currently have more than 100 taking part – and every single hour helps.

Training is free and after three hours they’re citizen scientists, ready to go out and survey some of the most beautiful places in Surrey, such as Chobham Common, Quarry Hangers and Puttenham Common. This year we aim to expand into other areas, including urban environments.

Each volunteer is assigned a designated area. Within a one-metre quadrat they use a simple smartphone app to identify plants, record the amount of bare ground, sward height, other interesting species, signs of grazing and so on. Cheat sheets and QR codes make the whole process really easy. For accuracy we need the plants to be in flower, so most of the work is done in spring and summer. Some people do it in pairs or groups, while others prefer to go solo. We have teenagers, pensioners and everyone in between.

Our volunteers are so positive and enthusiastic, it’s wonderful. Forty-two of them came to our open forum event last summer to hear the S4N partners explain their roles. The University of Surrey presentation on satellites and data feeds was particularly popular. It’s also fantastic to see them developing their skills and becoming recorders of more detailed wildlife information. We’re delighted to get closer to our target of one in four people taking action for nature.