This dissertation project formed part of my studies as an MSc Student at Birkbeck College, University of London. I was interested in addressing biodiversity decline in England, where insufficient space for large, protected wilderness areas means land must perform multiple functions combining nature conservation with other purposes such as agriculture or outdoor recreation. I came across SANG whilst reviewing the 2021/22 Surrey Wildlife Trust research prospectus and saw a potential example of this dual functionality which I could investigate.

Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspaces (SANG) arise from the requirement on planning authorities in England to mitigate the impact of development on biodiversity. They were devised as part of a suite of measures to address this around the Thames Basin Heaths (TBH), a special protection area (SPA) which includes habitat for rare ground nesting birds. SANG must be provided by any new housing development within 5km of the heaths to redirect additional footfall from new residents away from the SPA and so reduce bird disturbance.

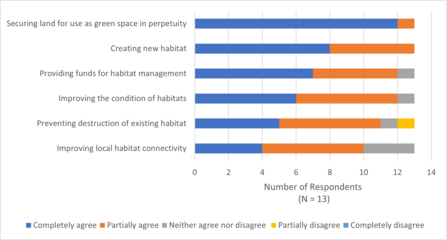

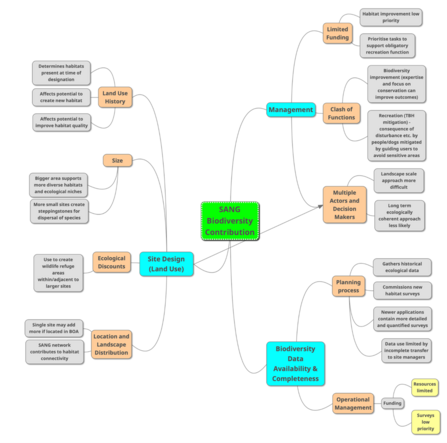

My project investigated the biodiversity potential of these green spaces in their own right, both individually and as a network, separate from the mitigation of damage to species found on the TBH. It looked at how SANG affects land use, how they are managed and the availability of biodiversity data relating to the sites. I gathered information over the first 6 month of 2023 using a variety of methods; a review of online resources and documentary evidence and a survey (13) and interviews (5) of members of the Thames Basin Heath Partnership (TBHP) to collect views of SANG managers, owners and advisers on the impact of SANG designation on site biodiversity.